Living vs. Surviving: An Analysis of Super Mario's Powerup System

Violence is a useful thing in drama. It's ancient, universal, simple, and engages the interactive side of our medium. When a player engages with this kind of conflict in a system that measures success and failure, the need arises for quantifiable measurements - abstracted simply, health.

Health in older games is often portrayed as a binary rather than a gradient. In such cases, wounds suffered by the player character do not impede their abilities; an injured adventurer can swing an axe as well as a healthy one, for example.

Studying how both health and ability track in gameplay systems allows us to paint a greater picture of the developer's intent regarding forgiveness and challenge in a game. Nintendo's Super Mario series, specifically, has a long history of experimenting with these elements across multiple titles and many decades.

Powerups as Aesthetic / Characterization

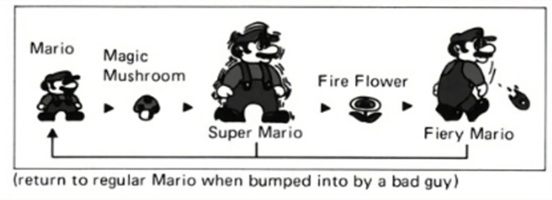

Quick summary! Super Mario Bros. (1985) established the definition of a powerup for the series: an item acquired during gameplay that provides a boon to the player. With the exception of timed or temporary powerups like Starman or the Hammer from Donkey Kong (1981), powerups are generally retained as long as the player is able to avoid damage (more on that later).

Another general rule is that powerups visually transform Mario, be it a costume, accessories, or a new color palette. These designs keep things cartoony and whimsical, but also conveniently keep the player's collider boundaries standardized. Later games experimented with widening these rules, but most powerups generally fall within these standards.

Powerups are explicitly magic, per the original instruction manuals, which frames the action as cartoony and avoids anything graphic like wounds. The greater effect of all this is to characterize the Mushroom Kingdom as a sort of magical playground - one where it's okay to laugh along while adventuring. Charms aside, Mario is a series ultimately about verbs, not adjectives, and while powerups serve well as tonesetters, their greatest usage is in utility.

Powerups as Exploration / Combat Modifiers

My interest with the powerup system lies with its ability to recontextualize the play space around Mario. Powerups often grant abilities with tremendous interplay between mobility, combat, and exploration, which encourage the player to notice otherwise unseen details and act as dramatic catalysts for situational risk and reward.

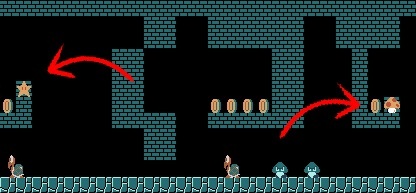

Nintendo realized the potential for powerups to be vectors of change as early as World 1-2 of SMB, where several hidden items can only be retrieved while powered up, and thus able to break blocks.

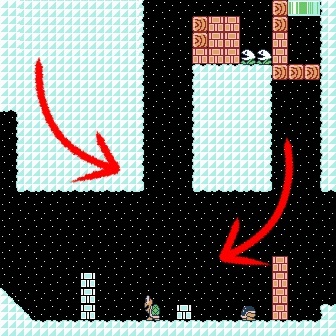

Originally used for simple secrets, the concept was further explored in levels like World 6-5 of Super Mario Bros. 3 (1989), where the vertical shaft leading to the exit could not be traversed without a flight powerup. The level features a looping pipe section which resets the level's blocks, so if the player loses their powerup, the level can be repeated as long as time remains.

Because of powerups' ability to affect play space, Nintendo quickly caught on with inserting moments where clumsy powerup usage can endanger the player. In these examples, the level design sets the tension, the player releases the tension with skillful play.

World 2-4 of New Super Mario Bros. (2006) features the Hammer Bros. (twin turtles that throw hammers) jumping between two horizontal rows of blocks. If the player has a Super Mushroom, they have the option of breaking the blocks to quickly reposition themself or create an opening to jump over the hazards, but they risk dropping a Bro from above, as it's always safer to engage a Bro from below, as hammers are thrown in a vertical arc.

Another example is World 6-10 of SMB3, where using fireballs to unfreeze the coins encased in ice can also unfreeze the sealed Munchers (reactivating their damage colliders). Note that the button to make Mario run is the same as the button to throw a fireball. If the player wants to exit the level to safety as quick as possible, they must be careful to orient Mario's direction and position correctly.

"Take risks to get rewards. This push and pull is the very core of game essence. It also has a big impact on what we call 'strategy.' Strategy is all about using ingenuity to reduce risks and get rewards. Risk and reward must be in close proximity, and in the right amounts. Always look for exciting ways to link the two and add twists." - Masahiro Sakurai

Powerups as Difficulty Modifiers

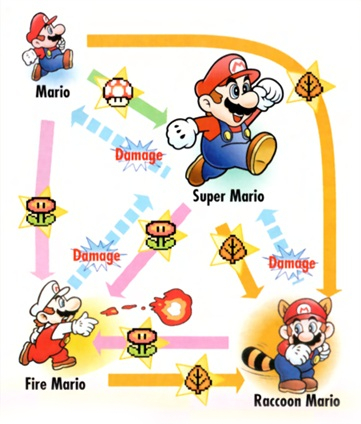

SMB established another caveat: taking damage removes powerups, resetting Mario to Small Mario status. Note that this happened even while powered up as Fire Mario.

This contributed to the toughness of early Mario games - powerups were scarce, and mistakes removed them promptly. The games have flip-flopped on the rules as they continued to experiment, but have since settled on more forgiving gameplay - players only descend one powerup tier at a time, and can restore powerup status more easily.

Later entries also cooled the pressure by expanding Mario's optional moveset: carrying and kicking Koopa Shells, Spin Jumps, Ground Pounds, and Wall Jumps, for example. This leaves Small Mario not nearly as helpless a state as before. Two details should be emphasized here: one, that Nintendo has created a system where Mario's core physical limits are reliable and predictable, regardless of powerup status (imagine a version of the games where the jumps could be made unclearable without powerups?), and two: that the vast majority of these games can be completed by simply running and jumping.

This all serves to give the player a fighting chance, regardless of the state the player finds themself in. That being said, the games are usually more fun with powerups: how do we get them?

Powerup Availability

SMB3 and SMW introduced three major changes to powerup accessibilty: the World Map, the Inventory, and the Stored Item, respectively. The World Map displays the individual levels as part of a larger area, the Inventory allows for players to hold powerups for later assignment through minigames and interactions on the world map, and the Stored Item allows for in-level usage of a second powerup, either automatically dispensing when the player was injured, or manually via a button press.

The World Map is a simple, but profound change: it turns the feeling of progression from a "no turning back now" march forward into a wider adventure - one where the player can have some more choice and be encouraged to revisit a level for the joy of it (fitting that it was introduced in the game where Mario starts the game explicitly on vacation). It encourages players to visualize levels from the context of the greater setting, and from SMW onward, replay previously completed ones.

Taking this point further, the challenge of using a specific powerup to obtain a collectible now has a new shape. The player is incentivized to both bring the correct powerup along, but also avoid damage long enough for it to be dispensed at the right time!

The Inventory gives players more freedom in what powerups are available at any given time - an idea that is doubled down on with the themed worlds of SMB3. World 3 of SMB3 is Water Land, for example, so one of the most common powerups found on the World Map is the Frog Suit. If the player wishes to use a Hammer Suit or Super Leaf, however, they can by pulling it from their Inventory. This also eases the sting of losing a life and being sent back to the World Map, as the player can now better equip for what lies ahead based on their first try at the level.

What I personally appreciate about the Stored Item is how it rewards skilled play. Whereas previously collecting a powerup while fully powered up did nothing, now it serves as an investment for when it is needed. There's even a small hint of strategy where players can be picky about what powerups to touch at all, as to not override their existing Stored Item. Furthermore, players can take note of crucial powerups in specific levels and replay them later to store them! Everything feeds into itself.

What We Can Learn

One could argue all of this is in service of a greater discussion on how each Mario title answers the question "how do you make a game where the player has one hit point beginner-friendly?" (to fully answer it would take several further pages of analysis and an addemdum on Yoshi). Needless to say, Nintendo is sympathetic to all skill levels, and generally tries to accomodate whenever they raise the skill floor. For example, when the final boss battle with Bowser was made into a multi-phase sequence in SMW, Nintendo also included Princess Peach to toss Super Mushrooms into the arena during the intermissions.

✔ Make things connect

In a series like Mario where the verbs for combat and exploration are the same, powerups create multiple points of interest: replay value, secret-collecting, and difficulty modification. Furthermore, everything within this ecosystem of values has ripple effects - gain the ability to fly to avoid fighting an enemy that's been giving you trouble, and open up new routes through the level as a result. All in service to the greater curiosity and delight of the experience - everything is connected!

✔ Empower the player

Some powerups can trivialize the challenge of a given level (or in the case of items like SMB3's P-Wings, are designed to do so). Nintendo, however, doesn't worry about players abusing this - instead banking on the fact that actually playing the game is more fun than skipping over it. Further mechanics even developed this as a minor strategic choice! If your abilities don't do exciting things, the player won't be excited to collect them.

✔ Make mundanity exciting

Lest we forget, everything discussed here could have been pips on a health meter. By choosing to create a system where the entire state of the game hinges around the player's health, Nintendo created gameplay where every hit matters.

"A good idea is something that does not solve just one single problem, but rather can solve multiple problems at once. It's easy for people to come up with a good idea that can focus on one problem, but that's not good enough." - Shigeru Miyamoto